Melany Bonilla Delgado

Undergraduate Recipient, Globalization Studies and International Relations

Guiliano Fellow, Fall 2024 "New Orleans; Le passé recontre the present" (New Orleans)

"New Orleans; Le passé recontre the present" (New Orleans)

On January 2nd, 2025, I flew to New Orleans just a day after the city had experienced a terrorist attack. After getting off the plane, I went to catch a bus that would take me to the hotel. I took one bus and then another, and then I got lost. It turned out the address available on the booking website was wrong, and I ended up on the other side of the city. But as I was walking through the area, it looked unexpectedly familiar. The houses were quite similar to those back in the countryside of my home country (the Dominican Republic). The small, colorful wooden houses reminded me so much of the Caribbean. Little did I know, they were actually related.

After I arrived at the hotel, I went right away to explore the French Quarter. The first thing I tried was Creole food. As I tasted the rice and beans, it truly reminded me of home. The bread pudding and the jambalaya were like a transportation to my island. The more I walked through the city, the more Spanish it looked to me. It was called the French Quarter, but it truly seemed like the Spanish Quarter to me. It turned out that the distinctive architecture of New Orleans was not French but Spanish, and there were only two buildings that possessed French architecture: the cathedral and the Old Ursulines Museum.

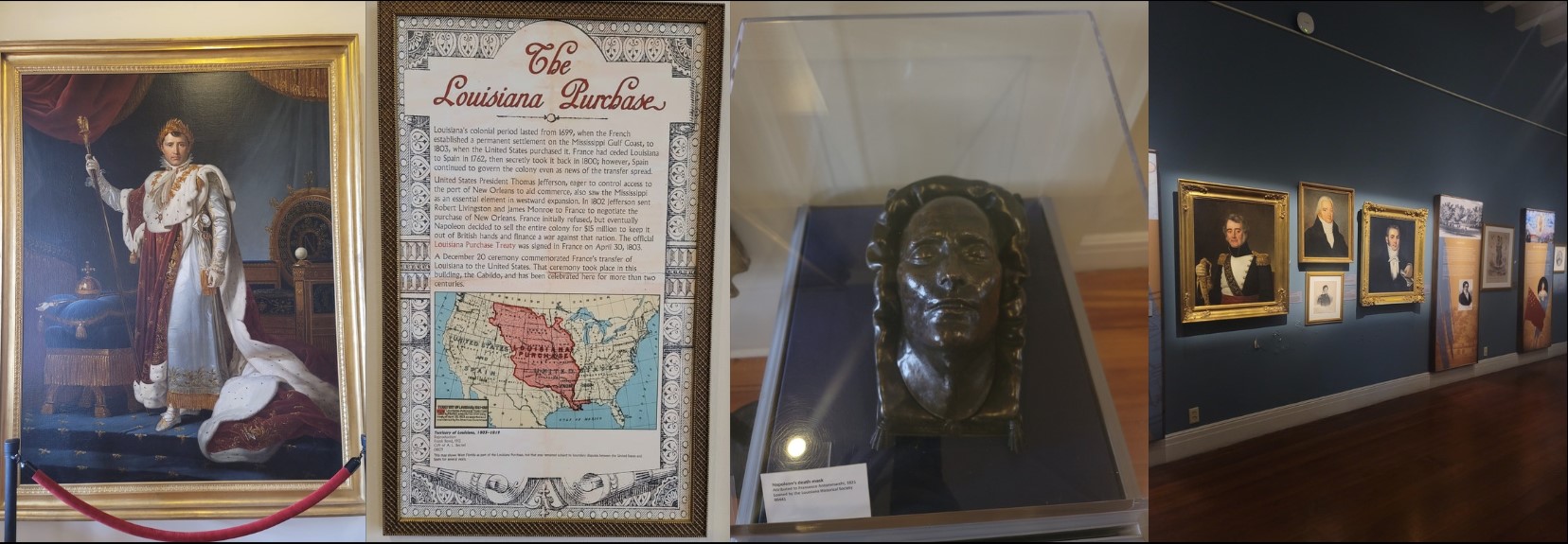

During my visit to the Old Ursuline Museum, I learned about the European history of

New Orleans. I discovered how the King of France ceded Louisiana to Spain and how

fires destroyed most of the French architecture. Interestingly, the Spanish later

demolished the remaining French buildings, believing they were responsible for the

fires.

I also explored the divisions that later emerged between Catholic Europeans and Protestants, with Canal Street serving as their neutral boundary. Additionally, I learned about the arrival of Italians and how they relied on the Church for protection and support to survive in various parts of the South.

One of the most fascinating aspects I encountered was the real reason why Spanish, French, and Italian cemeteries feature above-ground tombs instead of traditional burials. While many assume this is due to New Orleans' high water table, it actually stems from the Catholic belief that bodies should rest above ground in mausoleums shaped like temples, venerating the soul of the deceased—a tradition that originated with the Greeks.

The second stop was Treme's Petit Jazz Museum, where, unfortunately, I could not take pictures, but I received an incredible history lesson from its owner. The owner, whose name I will withhold, is of African-American and Cuban ancestry and has always remained deeply connected to Caribbean and Latino culture. His grandfather taught him Spanish, which allowed him to explore the roots of jazz in Cuba.

He explained how many Haitian women insisted that their husbands put houses under their names, leading to a significant number of women-owned buildings and homes in Treme—well before this was common in other parts of the United States. He also clarified that although Treme might not be the first Black neighborhood, it was the first integrated neighborhood in the U.S., as many white and Black immigrants from the Caribbean settled there. This explains the notably large biracial (Black and white) population in New Orleans. This racial mixture is something very common among latino and caribbean countries which also showcases the caribbean influences in the city.

Music in New Orleans is also something to experience. There is truly music everywhere in the French Quarter. Jazz is widely played by everyone, and wherever I looked, there was art, a historic site, music, or all three. However, it was interesting to discover that genres like rock and roll were also born in New Orleans, though these genres gained widespread fame only after they were performed by white singers.

Addressing more of the Caribbean influence in New Orleans, Vodou is the tradition that takes the lead. Vodou originated in Haiti, emerging from a blend of West African and Catholic traditions, creating a unique religion that honors and respects African ancestry. The Igbo and Yoruba traditions are the most prominently represented in Vodou. This religion was brought to New Orleans by Haitians during and after the Haitian Revolution, when they fled the island due to political instability and danger. Vodou has not only become an essential part of New Orleans' cultural traditions but also remains a religion that is actively practiced and respected today. New Orleans is home to Vodou Queens, festivals, and sacred sites. Vodou shops and practices can be found throughout the city, showcasing its enduring influence.

Initially, I went to New Orleans because I was curious about its unique mixture of

cultures, but I ended up discovering much more—even about my own country. This photography

research project has truly inspired me to continue conducting cultural research and

to keep uncovering extraordinary facts about places like New Orleans.

The Guiliano Global Fellowship Program offers students the opportunity to carry out

research, creative expression and cultural activities for personal development through

traveling outside of their comfort zone.

GRADUATE STUDENT APPLICATION INFORMATION

UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT APPLICATION INFORMATION

Application Deadlines:

Fall deadline: October 1 (Projects will take place during the Winter Session or spring semester)

Spring deadline: March 1 (Projects will take place during the Summer Session or fall semester)

Please submit any questions here.